Previously on “Mini-Memoir of Resistance”: After an intense campaign, the mayor of New Brunswick, NJ, allowed the men’s shelter to reopen in September 1986.

There are only two more actions I want to describe as part of my “mini-memoir” during this month of almost-daily posts. Luckily, there are only two more days left in the month. I do feel uncomfortable writing about myself so much, but these are the stories I’ve got. I tried to make this one short, but it kept growing. And I’ve been sleep deprived, so I’m not editing this as much as usual.

Assuming no one really wants to read so much, here’s the TL;DR. And there are a couple photos below.

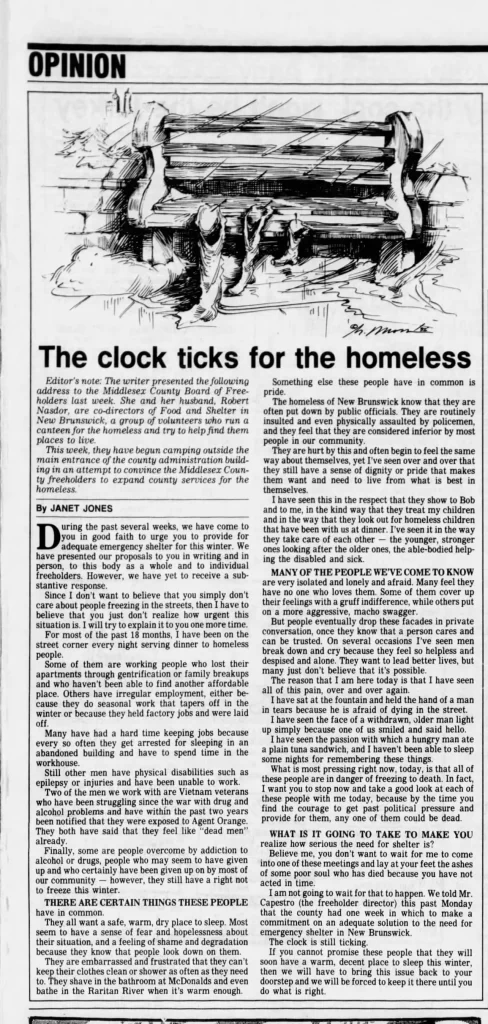

TL;DR: A year after the shelter re-opened, there was still a clear need for more space. We lobbied the county government to do something. After they dragged their feet for too long, we camped on their doorstep. Other activists and some unhoused men and women joined us. Police chased us out 12 days later. A couple weeks after that, the county gave money to Catholic Charities to put people in motels over the winter.

11. With the shelter struggle won, my husband went back to full-time operation of our nonprofit “movement” print shop. I was tired of teaching writing. I’d landed one of my most enjoyable jobs ever – researcher for historian/author Martin Duberman’s final edits on what was then the definitive biography of Paul Robeson, with full access for the first time to family papers and interviews, FBI files, etc. I spent a lot of time at the Princeton U library. Duberman didn’t have much info on Robeson’s childhood. Since he had grown up in Princeton and in Somerville, not far from New Brunswick, I thought I could use other local resources to find out more. Duberman agreed to pay me to investigate. At the time, New Jersey towns typically had weekly newspapers focused on local interests. I went through the archives for both Princeton and Somerville, using those cumbersome microfilm machines that made me dizzy as I whirred past pages of want ads and such. Robeson’s father was a minister, so sometimes there were church mentions. I found a few references to Paul himself in school or sports activities. I also tracked down Robeson’s childhood friend, then an elderly woman, and interviewed her. All told, I didn’t find a ton of info, but it was enough that Duberman was happy to build out his first chapter.

12. But I digress. After the shelter opened, we stopped serving dinner, but within days it was clear more people still needed it. So we started that again and decided to name our efforts Food & Shelter. I was no longer making and serving food alone, since the publicity of the shelter campaign had brought out a retired couple, a fantastic group of college-student activists who called themselves RU with the Homeless, and a church group, who each took a night a week. (All told, we were outside seven nights a week for 18 months, then one church invited people in three nights; a few months later another church took the remaining days with the dedicated help of the college students.) At some point I’d like to write about that 18 months, because the experience was simultaneously challenging, rewarding, and entertaining.

Our dinner continued to attract single men. Maybe a woman showed up once in a very-rare while. The shelter had only taken 20 men off the street, and clearly more were in need. The closed hotel continued to be used. On one cold, rainy night when only two men and I were at dinner, I said we should take food in the hotel, but the men said absolutely not, that I was never to go in there, especially alone, because it wasn’t safe. So I never got to see it, but I have imagined it a lot, particularly since the novel that I’ve puttered with over the years has a critical scene in the hotel.

On advice from more experienced activists in Elizabeth, NJ, we started accompanying men to the City welfare office to advocate for emergency motel placement which many were entitled to by law. It was common for welfare offices to deny people improperly. We took a copy of the state’s administrative code governing who was eligible. We were polite and reasonable in arguing with the welfare folks, but we got as pushy as we needed to. We never were arrested, though a few times the City welfare director threated to call the police and maybe did once, just because we were a pain in the butt. But by this time, the winter of ‘86-87, we’d been threatened so many times that we just told them, “Go ahead.” Anyway, one by one people got motel rooms this way.

13. But a lot of people weren’t eligible and continued to come to dinner with no safe place to go afterward. One snowy February night when I was serving alone, I was so sad and furious as I watched the men walk away. I was venting to Ed, the one remaining man, feeling pressure in my chest, and that’s when the sentence I posted about on November 21 popped into my head: The antidote to despair is resistance.* I stashed my giant soup pot in my nearby car and asked Ed if he wanted to go with me to the Middlesex County Administration building, a few blocks away, where for some reason I knew a Freeholders’ (county government) meeting was happening.

I’d never been to one and didn’t know how it would work, but I needed to tell them to do something for the people left out of the shelter. I’m a pretty shy person; during our shelter fight, I’d often had my husband be the public face, even though we strategized and crafted statements together. But he was home with the kids that night, and I couldn’t take the despair any longer.

The meeting was crowded. I recognized some audience members who had supported our shelter campaign. I was both buoyed by their presence and afraid I’d embarrass myself in a big way. When public comment time came, I stood up and said the Freeholders should give us the lobby of the building immediately as an emergency shelter. The building was already open, heated, and staffed 24/7. I said we’d provide bedding and volunteer supervision and would clean up each morning. I told them how this was being done in other US cities. My voice shook throughout, which embarrassed me more. But that felt better than the despair of doing nothing.

They received me politely and said they’d consider it, though no one there believed that. One of them offered Ed a job. They were well aware of our fight with the mayor the previous summer…the county building was across the street from City Hall. They chose a different demeanor than the mayor had.

I left the meeting before it was over and was surprised when a handful of reporters followed me out. I hadn’t thought about press. But they found it interesting, and a couple articles appeared the next day. Nothing came from the meeting, other than a face-to-face introduction with the Freeholders and notice to the public that there still was a problem.

14. Through the following months we continued our welfare advocacy and dinner. In the summer Mitch Snyder called to say he was arranging for groups to rent trailers to house people during the coming winter. We’d just have to find $35,000 and a place to put them and round up volunteers for staff. Logistically, it sounded like it would suck to run, but we recognized it was a solution. We spent a few months trying to find land. A church offered some, but it fell through. We went back to the County Freeholders and asked for the money and some land. This went round and round, private meetings and public meetings. Wishy-washy statements but no results.

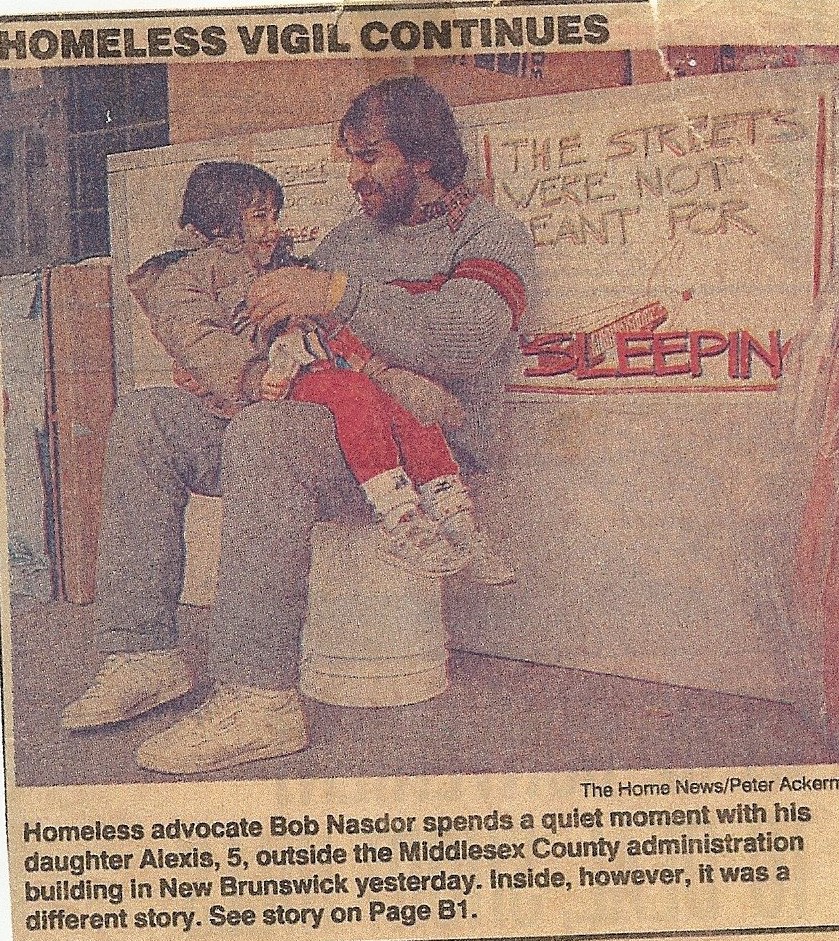

By November, my husband and I were tired of trying to persuade others to do something and didn’t want a drawn-out campaign like with the shelter. We decided to escalate our own activism: instead of another rally to pressure the Freeholders, two days before Thanksgiving we held a press conference to say we were going to camp on the Freeholders’ doorstep. We had two refrigerator boxes: one for us and one for two friends. We expected to be arrested, but no one bothered us.

(This is the statement I read at the press conference. I handed copies to the reporters so they’d quote accurately. The following Sunday, this paper, the Courier-News, ran an editorial supporting us and surprised me by printing my speech.)

On the second night, the encampment grew with more students and some of the men from dinner. We began to serve food there instead of at the fountain.

The night after that, two women we’d never met showed up. They’d been living in a park and heard about us and were relieved to have a place to sleep where they could feel safe. Our protest was becoming a shelter. We’d never imagined this.

After seeing the public relations debacle the mayor had caused for himself, the Freeholders didn’t want to arrest us and let us stay, allowing more good press. We got a lot of community support, though some of the mayor’s supporters condemned us. He was still mad; he publicly accused my husband and me of “feathering [our] nest with twenty-dollar bills.” We just laughed at how pathetic he sounded.

Our encampment went on for 12 days. By now 15 people were sleeping there. When we could find an overnight babysitter, my husband and I would stay together. Usually we alternated nights. Early one morning I woke up and stumbled my way to McDonald’s to use the bathroom. When I came back, I found the police chasing everyone away. They had caught one of the men peeing against the building** and used that as an excuse to shut us down. In my still-half-asleep bewilderment, I just stood there and watched instead of doing what I should have: organizing anyone who wanted to to sit down and refuse to leave. I was the last one to drag my box out of there.

When I got home and told my husband, he was livid that I’d allowed our protest to be destroyed, that I hadn’t controlled how it would end. That evening, in tears, I grabbed a sleeping bag and went back. I didn’t have the box anymore, and I was by myself. I was able to park right in front of the entrance where we’d camped out. But I was afraid to sit out there alone all night. I spent the night in the car, accomplishing exactly nothing.

A couple weeks after they chased us out, the Freeholders allocated $80,000 to house people in motels over the winter. They contracted with Catholic Charities to manage the process.

New Brunswick had no motels – only the expensive Hyatt Hotel across the street from the J&J lawn we’d camped out on and the closed VIP hotel where men continued to live. The motels were anywhere from five to thirteen miles out of town. So every night after dinner, RU with the Homeless, some friends, and I would deliver carloads of men to their destinations for the night.

As I checked the newspaper archives tonight, I saw I’d forgotten the many meetings and smaller protests held during the course of this Freeholder campaign. And I’d forgotten how much we pissed off both the County and Catholic Charities. We could be obnoxious. They criticized us a lot in the press. But apparently that was the price for getting results.

Next: Final Memory – one year later, occupation of unused federal land ends in our being the first group in the country to get such land to build housing. No one is more surprised than we are.

*https://janetjonesbann.substack.com/publish/posts/detail/151964778?referrer=%2Fpublish%2Fposts

**I didn’t have sense enough then to recognize the privilege I had to be able to go to the bathroom at McDonald’s and not be chased out. I think I bought access with a cup of tea. People living outdoors typically don’t have bathrooms available.