Context: This post is part of a series of blurbs I wrote tracking my history of activism before family and the need to make more money interfered. It starts with my Nov 17 post. With this post, I finally give up the weird second-person narrative that it originally came out in.

I learned a lot in my years as an activist. By the time the summer I describe here came along, I’d been at it 7 years. But my first critical lessons came during this summer.

Previously on “Mini-Memoir of Resistance”: Twenty-three of us must prepare for our trial after being arrested for the tent city on Johnson & Johnson’s lawn. I’ve begun to make dinner every night for the dozen or so unhoused men who are hoping these protest actions will get their shelter open again.

8. Epiphany! Don’t be an asshole: With the trial a few weeks away, I start writing my court testimony. Somewhere between that lofty speech and ongoing dinners with the men, I realize I’m a total fraud if I don’t stop thinking of this as a one-and-done, fun civil disobedience action and realize it’s dead serious for the men. But I don’t know what to do – none of my activism has ever accomplished anything I wanted it to. It hits me hard that I have to make this shelter fight my fight, in a way I’ve never done with anything before, or I’ll be a big hypocrite.*

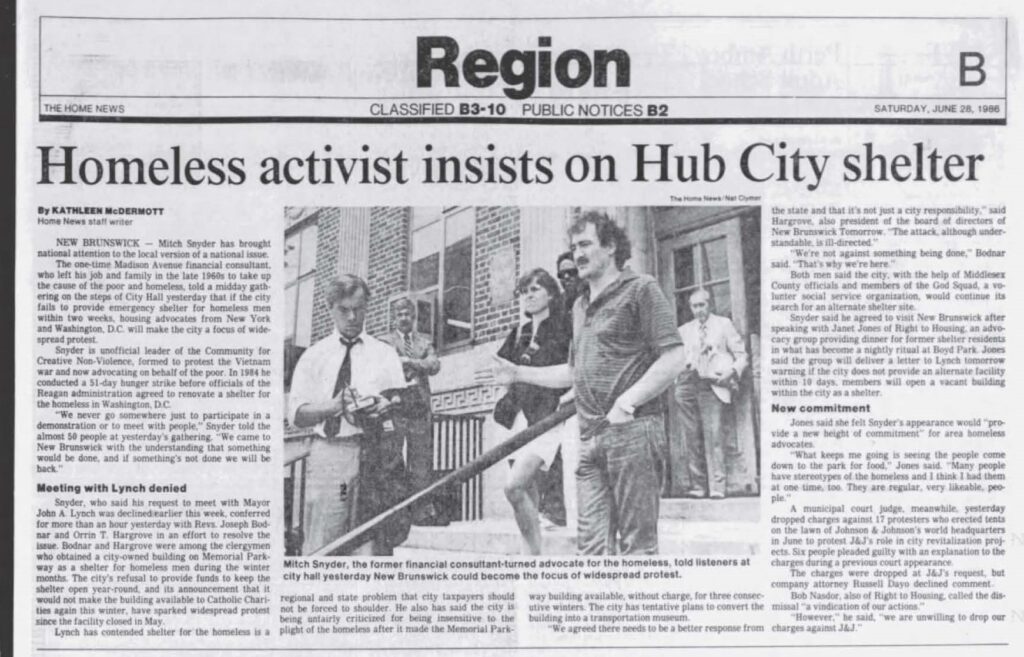

Back in 1981 at the Plowshares 8 Support Committee office, Mitch Snyder of the DC-based Community for Creative Nonviolence** came in to get a copy of our mailing list. I’d admired his work from afar and had started paying more attention.

Now I need expert witnesses for the trial, so I call Mitch. He says, “Sure. But first…” and tells me to give the mayor a letter saying if he doesn’t open the shelter immediately, we’ll open it ourselves. As in: break in and plan to spend the night.

9. I evaluate my nonexistent courage. Take a deep breath and move forward anyway: I hang up and tell my husband, and the two of us freak out because we know if we start this process…deliver such a letter…we must follow it through to whatever end it takes. We type the letter on our little Apple IIc, rip off those hole-punched edges of the dot-matrix paper, sign it together, and take it to City Hall. We call the press and read it to them.

Thus begins a three-month series of highly publicized actions to force the mayor to open the shelter. When the trial date arrives, Mitch comes to do a press conference at City Hall and to testify, but J&J drops the charges. No trial after all.

The mayor, embarrassed by ongoing negative press, has sputtered about how the City has done enough already but appoints a panel to recommend what he should do. They say open the shelter, but he continues to sputter. We give him another letter saying he has 10 days to open it, or we’ll turn an abandoned building into one. He makes wishy-washy promises in the press; we’re impatient but have to give him a few weeks to keep those promises. We don’t think he will, but we must let it play out.

Simultaneously, we do other things that result in the state pledging operations money for the shelter and Catholic Charities agreeing to continue to run it. (It isn’t clear they want to. The nun in charge is pretty annoyed with our shenanigans.)

10. Enough already…three intense days. We get fed up and tell the mayor/press we’ll hold civil disobedience actions every day until he opens the shelter. Included in that letter is a statement from Mitch Snyder: if necessary he’ll return to New Brunswick with Dick Gregory & some Hollywood friends to camp at City Hall & that if they’re arrested, they’ll just keep coming back.

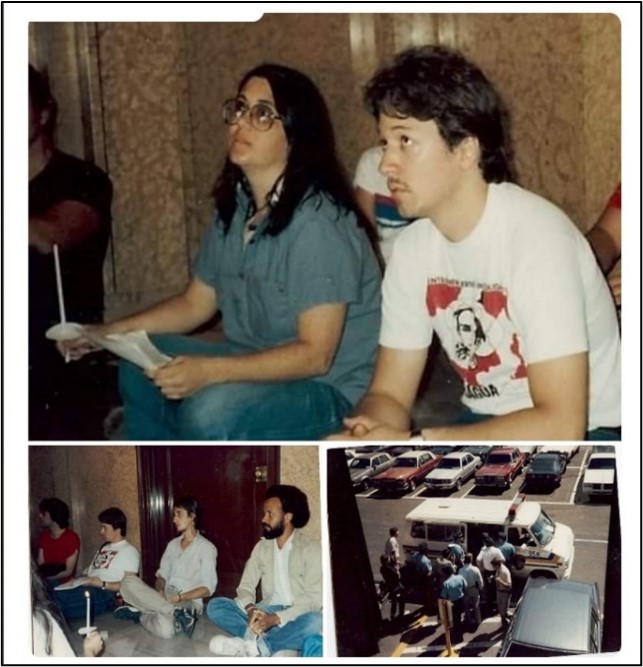

On 9/9/86, day one of the plan, several of us hold a prayer vigil/sit-in in the hallway near the mayor’s office. Six of us are arrested. In the photos below, the police chief is warning us to leave and we’re being put into a police van.

That same day, the article below comes out. The night before, my husband and some of the unhoused men had taken a reporter through the closed hotel that had formerly housed 139 low-income people. The hotel has become a de facto shelter. As the article states, both the owner of the hotel and the man buying it know people are living there. They say the City knows it too, and no one cares.

It’s a judgment call, with consent of the men organizing with us, to put the spotlight on where people go without a legitimate shelter. (Previously, my husband and I and some of the men had taken that reporter into an abandoned house where they were staying. That produced another article embarrassing the mayor.) This article has the effect we want: putting more pressure on the City. Predictably, the police raid the hotel the next night. Nine men are arrested. In the 9/11 article covering those arrests, a spokesperson for the mayor accuses my husband and me of importing homeless men to make the city’s issue appear larger than it is. 🙄 When asked for comment, my husband is quoted, “That’s too stupid to respond to.”

Also on the evening of the 10th, several of us set up camp on the City Hall lawn. Seven are arrested. The women are strip-searched, ending in a lawsuit and national coverage. On the 11th, my husband goes into the mayor’s office to ask for a meeting and sits down to wait. He’s arrested and spends the night in jail, reuniting with dinner guests happy to see him.

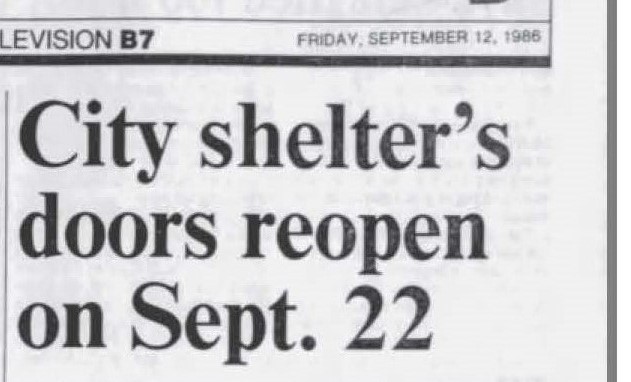

The next day this article comes out

It takes several civil disobedience actions, including some not covered here; a protracted campaign of keeping stories in the press several times a week; the help of a nationally known advocate; and making so, so many sandwiches for people every night. (My 18-month-old daughter’s first sentence is, “I want a sandwich,” a testament to how much time she spends at my feet as I plaster together tuna or egg salad and bread.)

But we win.

Catholic Charities opens the shelter on the promised date.*** That night I bring the men a sheet cake inscribed, “Not another night without shelter.” I don’t stay long because it’s clear the nun in charge wants me to go. But the men and I have our moment of shared celebration.

After they close the door behind me, I stand on the porch and take a few deep breaths. I’m happy. I believe this part of my life is over.

*Remember when being a hypocrite was a bad thing?

** More info: https://humanitiestruck.com/allexhibits/resistance-revolution/

***Thirty-eight years later, the shelter still exists with the need greater now than ever.