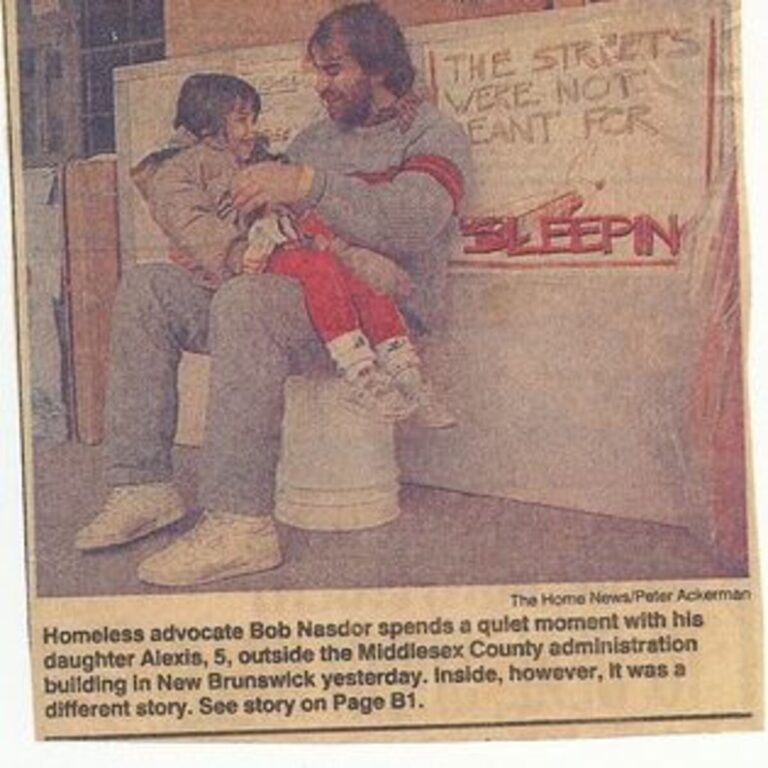

This photo (very blurry once I enlarged it) is from Thanksgiving week 1987, a combined few days of my daughter’s 5th birthday and the start of our second direct action campaign in New Brunswick, NJ.

That fall my then-husband and I had signed on to the Community for Creative Nonviolence’s campaign to get trailers set up around the country for emergency shelter for the quickly approaching winter. We asked the Middlesex County Board of Freeholders for money – $35K, I think – and temporary use of land to set up a shelter we’d staff with volunteers. They kept saying no.

During spring and summer 1986, we’d had a very public fight with the mayor of New Brunswick (situated, as he was, across the street from the Freeholders) to get him to rescind his decree that the city’s shelter for men would stay closed. We’d won that battle in September ’86 and had spent the months between then and Thanksgiving ’87 still serving dinner each night outside and during the day helping anyone we could to get shelter by using the state’s emergency assistance laws to push the City or County to put people in motels. The re-opened shelter was full, and several people who regularly had dinner with us had been banned, anyway.

We were tired…doing this work every day, running a left-wing print shop, caring for Alexis and Kara, our two-year-old. We didn’t have the energy for another drawn-out shelter campaign; with winter coming, we didn’t have time, either.

The previous winter Carol Fennelly and Mitch Snyder of CCNV had run a very successful campaign to get Congress to pass the unique and pivotal Stewart B. McKinney Homeless Assistance Act. They’d organized a sleep-out on the steps of Congress to ratchet up the pressure. It got national attention, building on their previous successful actions, and bringing Martin Sheen, Cher, and other celebrities. I think they started before Thanksgiving ’86 and camped out until the bill passed in April ’87…I remember calling Mitch to congratulate them from the New Brunswick courthouse where we were having our trials from our civil disobedience actions the year before. Carol can correct me if I’m wrong.

I raise this because when November ’87 came with stubborn refusal of help from the Freeholders, my husband and I decided all we had the energy for was to plant ourselves on the County Administration Building’s doorstep with a refrigerator box. We had a press conference to announce our plan to stay there until the Freeholders made additional shelter possible. Because our shelter campaign against the City had generated so much publicity, it was easy to get the central Jersey press and the statewide paper to show up.

New Brunswick is home to Rutgers University. The previous year a group of energetic, big-hearted students formed an organization, RU with the Homeless, to support our work. They helped with dinner, and a couple of members wanted to camp out with us. As I recall, there was still an appliance store downtown, so we got a handful of refrigerator boxes.

A couple of the men who needed shelter and who had been dining with us every night wanted to stay with us too.

We expected to get arrested…that the county would call the police, who would order us to leave, and then we’d say, “No. Not until there’s more shelter.”

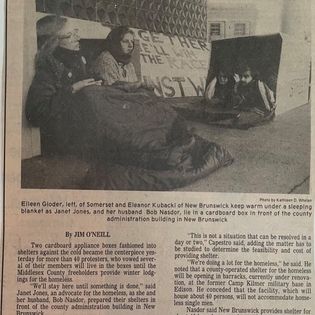

But nothing happened that first night. The next day, more people joined us. Within a couple days, when it appeared there would be no police response, more people who needed shelter came to sleep there with us. Most were men we knew from dinner, but a couple new women showed up, too. They had been sleeping in a park.

I was amazed that in the midst of our activist campaign, while we continued communication with the Freeholders and had more press attention, including the NBC affiliate from New York City, we had unexpectedly created a shelter space where people felt safe. It was completely inadequate – sleeping bags and refrigerator boxes – but it was a spirited community of about a dozen unsheltered people and activists.

We remained camped out for 12 days. Sometimes my husband and I stayed together in our box, but most nights we traded off because of the kids. It was my turn to be at the camp on the 12th night. Early the next morning I walked the couple blocks to McDonald’s to use the bathroom and came back to find the police rousting everyone out of the area. In my absence, one of the men had peed near the building – a reality of having no house or shelter is also having no bathroom. I was dense and didn’t recognize my privilege of being able to use the McDonald’s bathroom without being thrown out. Anyway, the police apparently were waiting for our group to make a mistake, anything they could chase us out for.

We complied and left. After so many days, we were tired.

A couple days later one of the men who’d become a regular at dinner died in the ivy outside that building, a victim of the cold.

A couple weeks later, the Freeholders allocated $80K for emergency shelter – not for us to use, of course – they were mad at us. They gave it to Catholic Charities, the organization whose shelter we’d resurrected the year before. The money was spent during the ’87-’88 winter to put people in motels.

That was a much better solution than our desire to run a shelter from a trailer. I was relieved. The motels were all outside of New Brunswick – one twelve miles away. Catholic Charities didn’t provide transportation, so each night after our dinner – which was still outside at that point – RU with the Homeless, some friends, and I drove people out to the motels.

The novel I’m getting close to finishing centers on a condensed combination of the campaign to get shelter, culminating in camping out. All wrapped in a romance. That part is pure fiction; if there was romance happening in our activist campaigns, I wasn’t seeing any of it. 😃