15. Finally, it’s the last day of National Blog Posting Month, the last day of what I tongue-in-cheek called my mini-memoir. As I mentioned at the start, I wrote this as a series of snippets for a class on writing & resistance. I never intended to do anything with it, but when faced with the need for 30 blog posts, this gave me an easy 7. My apologies that this one is kind of rough…last minute and not much time to polish.

So far I’ve described two civil disobedience campaigns my then-husband, some friends, and I undertook to get men shelter. (It was men because that’s who we encountered.)

Starting out, we never expected to do more than call attention to homelessness and pressure politicians to do more. But because the men had lost their access to dinner when their shelter closed, we started providing it. The first night, it was an organizing tool to get them to come to a meeting. Then it became clear it was a need we could figure out how to fill. And once we were serving dinner every night, we saw it also was a public relations tool, a daily concrete activity that other people noticed and that underscored the regular newspaper articles about the shelter struggle.

Our resistance actions expanded into direct service, similar on a very tiny scale to the work of the Community for Creative Nonviolence and the Catholic Worker. The two threads, resistance and direct service, wove together and drifted apart for the 10 years I spent doing this work. Activism is necessary for progress, but so are daily food, shelter, and other needs that our society makes it hard or impossible for some people to access.

16. In my last post I described our work to get more shelter during the winter of 1987-88. During that time we incorporated as a nonprofit and set up an office in a church basement. From there we ran the Homeless Outreach Center (terrible name, but we didn’t know better), from which we worked the phones and went to welfare offices to get emergency help for people one at a time. Four evenings a week we managed dinner at another church. And we continued to drive people to motels.

In May I got a call from the NJ Division of Youth & Family Services saying they had a mother with five kids who were about to be placed in foster care because they had no where to go. They’d used up their time at Catholic Charities’ family shelter and had used the five months of motel time the welfare agency was obliged to give them. The kids were going to be taken the next day, and in a last-resort call, the DYFS worker wanted to know if I had a solution.

I didn’t. But a rabbi had told me to call him if I ever needed anything, so I did. He offered his synagogue’s education building as an overnight shelter. We weren’t equipped for this. My husband and I had an extra futon that we hauled out there – the building was 15 miles from our home base of New Brunswick – and set up for the family. We must have had sleeping bags and maybe a crib mattress. I don’t remember. My family and I stayed with them that first night, then brought the family back into New Brunswick the next day to the mom’s sister’s apartment, where three families were already living. Suddenly we were running a shelter, meaning we had 24/7 operations. The wonderful RU with the Homeless students and a couple other friends came to our rescue and took turns helping us chaperone the family.

Catholic Charities’ family shelter was in a building that served as a summer camp, which meant it had to close every summer. The next thing we knew, 13 of those families came to us. The Red Cross gave us cots. I scrounged everything else we needed. The students got a Rutgers van and drove the families to and from New Brunswick every day. I figured out how to get the County welfare agency to pay us per family for each night of shelter, so we had some operating money.

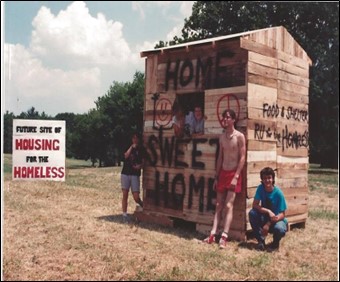

17. Also around May, Mitch Snyder called to say CCNV was organizing a national day to occupy unused federal land, and did we want to participate? The legislation they’d had passed by Congress the year before said the government needed to make vacant properties available to house people. It had been ignored. They were suing the feds but needed a public campaign. We agreed to become part of the lawsuit. Then we found 10 unused golf-course acres on a former military base in Edison, the same town as our shelter. The plan for the July 14 action day was to erect a sign, build a hut, get some press coverage, and hope we’d get through the day without a trespass arrest. We were meticulous and ridiculous in our planning, coordinating with walkie-talkies to keep a lookout for the police so we’d have time to build that shed pictured above.

It turned out the local police didn’t have jurisdiction, so the federal police had to come down from New York. They were in no hurry, so most of the day went undisturbed. They came in, told us to get rid of everything when we were done. But before they left, my husband gave them a letter he’d written to the Secretary of HUD demanding the property be given to us to build transitional housing for families. I knew he was going to do that – he’d been talking about it for days – and I thought it was an irritating distraction. What with running our outreach center, supervising dinner, and running our shelter at night, I had nothing left for fantasies.

We wrapped up the day peacefully, cleaned our trash, and left the sign and hut.

After that, things got weird. The lawsuit was moving fast, something I was barely aware of, consumed as I was by day-to-day operations. I was contacted by staffers for some Congressional committee and asked to testify about the problems facing homeless families in our area and why we needed that land to house them. I said my husband would do it (again, I was too shy). So the staffers visited us, and we took them on a tour of the land and the rundown motels where County welfare sent families when the shelter was full. We probably showed them our makeshift shelter, too. They went away and scheduled the hearing, and I helped my husband write his testimony.

That hearing took place in DC at the Capitol, and a few months later we became the first group in the country to be awarded land under that federal law. We were granted a 20-year lease for 3 golf-course acres and built this:

Amandla Crossing Transitional Housing opened in July 1991, three years after we erected the hut. What you’re seeing are six apartment buildings (30 total units) connected to a service building that included offices, a large library/classroom, and a licensed day care center. The one main entrance around the front opened into a huge, welcoming community living room. For complicated financial reasons, our program served only unhoused families on welfare.

While my then-husband was in charge of the building getting built, I designed the program with research and help from other people. But largely I went on instinct formed from the convergence of my major in Women’s Studies, my teaching experience, my activism education and experience, and my experience having been in therapy for a couple years.

Back then I was able to make the program be only for single moms and their kids. “Amandla” was chosen by our board because it means “power” in Zulu. I was good with that. The women in our program were under the often-dehumanizing control of welfare, and most had come from abusive relationships. I wanted them to be the authority, the head-of-household in their new apartments. Our rinky-dink family shelter had hosted one husband and wife, and I didn’t like the power dynamic I observed. I did not want to bring that into Amandla.

I could go on about Amandla forever, but I’ll wrap this up with just a few more thoughts. I lived with my family at Amandla for its first two years. I was the director, and as such I wanted to know the place inside out, 24/7. My kids were in 1st and 4th grades, and the multicultural environment was great for them. The fact that I continued to be a workaholic was not. That’s one of my life regrets, that my kids didn’t get the attention they should have because I was so involved in other things. I’ve apologized (for what good that does) a couple of times, and they tell me it’s ok because all this activism gave them their values. That’s generous of them, and I have to say they do have wonderful values. Still…

I burned out after five years – a total of 10 years working on the issue – and left Amandla to other people. It continued for another twenty years as transitional housing (meaning families were time-limited in their stays). Now it’s permanent supportive housing, meaning families can keep their apartments and there are services on site.

18. This whole series was supposed to be about resistance. I became so buried in work that it was hard to have time to participate in the other issues of the day. But I would argue Amandla’s foundation was resistance to what people thought of and expected of women living in poverty. I spent five years fighting the welfare system over that. It’s part of what wore me out.

19. The stories I’ve told you happened half my lifetime ago. So what have I done lately? Nothing, really. I’m going to quote myself from my blog post of 11/21/24:

I’m 70 and don’t have much energy. I’m too comfortable hanging out with my little dog and escaping with TV. I haven’t done anything in years, beyond the Women’s March, donating to the ACLU, and some pre-election work. I don’t feel like doing anything hard. But things are horrendous now in Gaza and elsewhere, on so many fronts in this country. And they’re about to get so much worse. I’m so worried for the trans and immigrant communities, in particular.

I have to take a hard look at who I am and what I am willing to stand for.

When Antifa was in the streets of Portland saying No and Fuck Off to Nazis et al, I wanted so badly to hop the Max and join them. I felt that pressure in the chest. But being older and too comfortable and scared I’d get my ass kicked in the first five minutes, I didn’t do anything but cheer them on. I’m not a brave person.

At my stage of life – at your stage of life – what does personal resistance look like, and when do we make it happen? What is strong enough action to make a difference? (I don’t think it’s only marches.)

Where does courage come from?

Thank you for reading.